Yesterday UK’s housing and planning minister Gavin Barwell announced that £7.4 million will be invested to support the delivery of new homes and settlements including 14 ‘garden villages’ and 3 ‘garden towns’. This, of course, prompted the Garden City debate once again.

I researched this subject extensively 2 years ago when the 100-year-old idea re-surfaced due to the Wolfson Economics Prize competition. Yesterday’s news got me obsessing about Garden Cities again so I decided to outline the common misconceptions about Ebenezer Howard’s model that I observe every single time the topic re-emerges.

1. Garden Cities are all about being green and sustainable

Misled by the word ‘garden’, the general public often imagines that Garden Cities are particularly green urban settlements with a lot of trees and vegetation. Yes, Garden Cities were supposed to be greener than 19th century industrial cities (which bare little resemblance to modern day cities in terms of health, greenery and cleanliness). The important point is, however, that greenery was never the real aim of Ebenezer Howard. It was simply a tool for the social reform he envisaged. The idea that urban environment is the vehicle for social transformation was soon criticized as deterministic and the efficacy or even desirability of social engineering was disputed. By the mid-1960s most planners acknowledged that ‘planned community alone cannot be expected to elevate morals or raise civic loyalty’ as Howard had hoped [4].

In addition, it must be mentioned that the only two Garden Cities built in the UK – Letchworth and Welwyn – have far less green areas than the author originally imagined.

The word sustainability was not part of Ebenezer Howard’s vocabulary 119 years ago but some professionals believe that modern-day environmental thinking is similar to the notions of combining town and country which defined the Garden City concept. However, it must be understood that Howard’s planning model stimulates urban sprawl. Urban sprawl and decentralized developments promote higher car use than compact dense cities. Howard’s model also requires building on greenfield land while there are brownfield sites available within cities. This is unsustainable not only in environmental terms, but also in social and economic terms because it ‘undermines urban amenities and communities’ [1].

2. Garden Cities are in fact Cities

Garden Cities are neither gardens (as pointed out in the previous paragraph) nor cities. Cities are amazing places – they are characterized by their vitality, diversity and economic success. By bringing a lot of people together they become incubators for new ideas and prosperity. This is achieved through their density and variety of functions. However, the concept of functional separation dominated the urban plan conceived by Ebenezer Howard for his Garden City. This idea devastated the ‘intricate, many-faceted, cultural life’ of existing cities [2] and prevented newly built Garden Cities of ever achieving the characteristics of successful cities mentioned above.

Therefore, it is understandable why the new settlements funded by the government are not branded as ‘garden cities’ but as ‘garden villages’.

3. Garden Cities are better than Cities

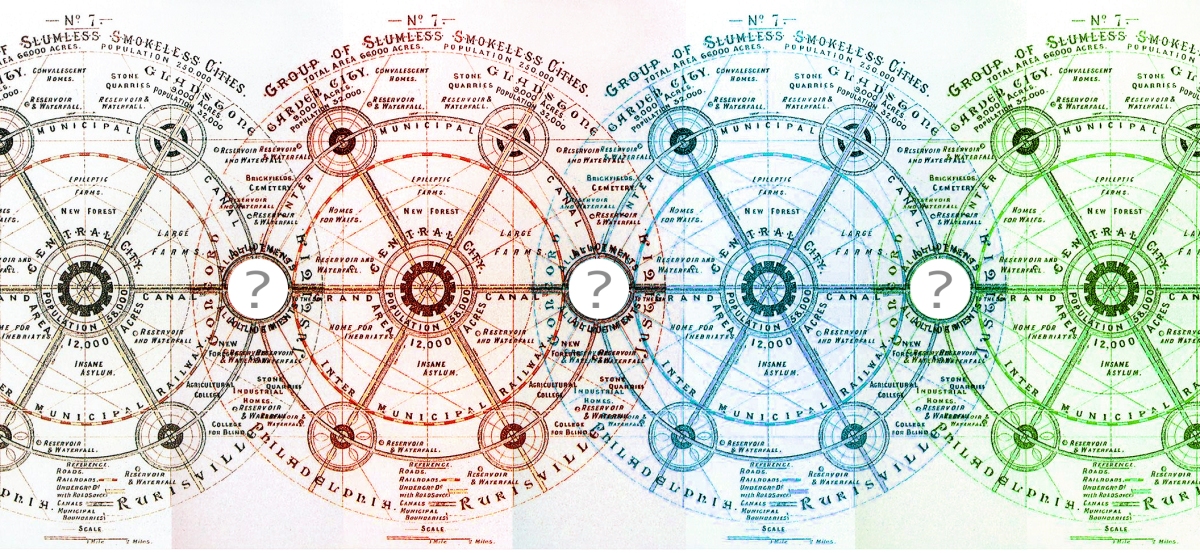

The exact physical form of the Garden City, as illustrated in Howard’s famous diagrams, has never been materialized for many reasons.

First of all, the idea of functional separation (also called zoning) has been widely disproved. The compactness and density of h

is Garden City have also been criticized because of the realization that for a settlement to be self-contained it must be relatively larger and denser than what Howard imagined, otherwise it would become no more than a commuter dormitory. According to some, ‘bounded communities on greenfield sites will necessarily be anti-urban in lifestyle regardless of the best intent of the designers’ [3].

The notion of building new settlements from scratch has also evoked many negative opinions. A city which is built up all at once and has not evolved organically is based on pretended order, it relies on top down planning and cannot provide something for everybody because it is not created by everybody [2].

In short, all main principles that defined the physical appearance of the Garden City have been disproved. It is not surprising that today planners learn from the mistakes of Garden Cities and study the success of real cities. The former are simply better.

4. Garden Cities mean beautiful Arts & Crafts homes

It is ironic that today most people associate Garden Cities with particular physical characteristics since Howard’s grand vision never focused on nice and pretty homes but on social reform (as mentioned in point #1) and community ownership.

The author saw the capturing of development value as the ‘crux’ of the Garden City model. However, the central principle of community ownership of the land was never realized in the way Howard described [5]. Consequently, the citizens of UK’s Garden Cities never benefited from the rise in land values as the author hoped [6].

The actual appearance of Garden Cities should be attributed not so much to Howard, but to architects Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin, who were supporters of the Arts & Crafts movement and became responsible for the design of the first Garden City (Letchworth).De facto, the book Garden Cities of To-morrow did not specify what the architecture of Garden Cities would look of feel like, it only provided a basic framework for their planning. The Garden City urban planning model was ‘almost incidental by-product’ [6] of Howard’s radical ideas, nevertheless, it remained a source of inspiration for planners throughout the 20th century.

5. Garden Cities are the solution to the current housing crisis

Ebenezer Howard envisioned Garden Cities as truly affordable places. However, the built Garden City interpretations proved to be homogeneous and exclusive neighbourhoods. Not only were they unsuccessful in improving the lives of the underprivileged but they also deepened the spatial and social division between wealthy people living in suburban peripheries and poor people situated in decaying urban areas. Author Guy Trangos even claims that the Garden City planning model later became an inspiration for apartheid governments in South Africa and Jewish/Palestinian separation in Israel [7].

Houses in Garden Cities can be quite expensive, and so is building a new city infrastructure from scratch. Therefore, it seems much more affordable both for the government and the general public to try to solve the housing crisis by proving new homes in existing settlements.

It should also be acknowledged that the Garden City was first conceived as an alternative to the dirty, unhealthy and isolating 19th century industrial city. Today, cities have improved a lot and by investing time, money and serious thought in them they can become even better.

Conclusions

Throughout the years, the Garden City model has proved to have a number of inherent flaws. Therefore, it always baffles me why we keep returning to this outdated concept. Haven’t we come up with anything better in the last 119 years?

In my opinion, the Garden City keeps resurfacing not because of the significance or quality of its principles but because of its inaccurate name that has led to many misinterpretations. Governments and private developers play on this confused public understanding and use the Garden City as a branding tool [8]. Thus, Howard’s revolutionary idea is reduced to no more than ‘a politically convenient fantasy’ [9].

Notes:

These conclusions refer to the original Garden City concept and the new government-led Garden Cities. They do not refer to the Garden City proposals generated through the Wolfson Economics Prize competition which actually show understanding of the advantages and flaws of the original idea.

Sources:

[1] Rogers, R. (2014) ‘Forget about greenfield sites, build in the cities.’ The Guardian. [Online] 15th July. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jul/15/greenfield-sites-cities-commuter-central-brownfield-sites

[2] Jacobs, J. (1993) The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Modern Library.

[3] Fishman, R. (2002) ‘The Bounded City.’ In Parsons, K.C. and Schuyler, D. (eds.) From Garden City to Green City: The Legacy of Ebenezer Howard. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

[4] Buder, S. (1990) Visionaries and planners: the garden city movement and the modern community. New York: Oxford University Press.

[5] Clavel, P. (2002) ‘Ebenezer Howard and Patrick Geddes: Two Approaches to City Development.’ In Parsons, K.C. and Schuyler, D. (eds.) From Garden City to Green City: The Legacy of Ebenezer Howard. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

[6] Ward, S.V. (2002) Planning the twentieth-century city: the advanced capitalist world. Chichester:Wiley.

[7] Trangos, G. (2014) ‘The dark side of Garden Cities.’ Architectural Review, 236(1412) pp. 20-21.

[8] Pullan, C. (2015) Garden Cities Workshop. Presentation at Urban Design Group, London, 18th March.

[9] Gibson, M. and Mason, L. (2015) ‘Fantasy or Opportunity?’ Urban Design Journal, (134) pp. 17-19.